This is post 3 / 6 of the Shadowing WPF 2024 series.

Borrowing Dulls the Edge

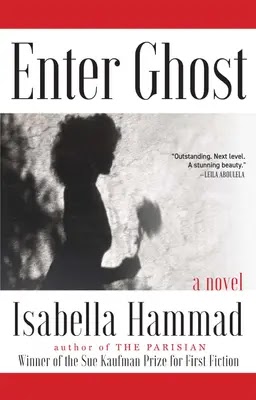

While some of the difficulties of daily experience are what readers would expect from a novel set between Haifa and the West Bank: checkpoints, interrogation, tear gas, rumour, violence, the most compelling moments in the novel come from exploring the effects of this context. Hammad shows us how these broader national politics affect everything from daily life, language and family politics, to different versions of history and a sense of personal authenticity.

Our narrator, Sonia, is a middle-aged English actor, a divorcee who recently failed an audition to play Gertrude for her ex-boyfriend at the National Theatre. She is visiting her sister in Israel, where they both spent their childhood summers. The opening is uncomfortable, with Sonia’s strip search at the airport, an awkward stand-off with a taxi driver, imagining her own suicide, protecting secrets from officers, her sister, the driver and the reader. Quite a lot is secret in this book - unspoken, unresolved - such as the full story of the casting of Ophelia.

Hammad’s style is a little elaborate for me, but it is effective. Verbs add to the drama of the opening, connoting sudden noise or violence: time to kill, water that crashed and cracked, jolting back, a body smashed, tank boats that cut, breeze that sliced. Even the sound of the first few pages is machine-gunned with plosives as she describes the setting: ‘Palm trees spiked the roadsides. Pine forests. Pylons.’

Sonia’s sister Haneen sums up much of the novel in their first conversation, when she explains that she feels she is ‘dodging bullets’ and doesn’t know ‘how to, how to be’. It is typical of their relationship that Haneen has booked theatre tickets for them and friend Mariam Mansour, not realising that Sonia is trying to escape the theatre. The play is excruciating to read on paper, but gets an enthusiastic response from the audience because as Mariam explains, everyone knows everyone here, which doesn’t make great art. This doesn’t bode well for Miriam’s production of Hamlet, the main event of the novel. Soon, we become aware of other members of Mariam’s family - Wael, a pop star who will play the lead and Salim, a suspended party member suspected of being a security threat. It quickly becomes clear that the play will be a struggle.

According to Mariam, ‘if we let disaster stand in our way we will never do anything. Every day here is a disaster.’ Her ability to switch from grief or concern to pragmatism is therefore necessary, but strikes Sonia as sociopathic. In this context, perhaps it makes sense that people often seem surprised when others reveal weakness. The compassion between acting and this defensive, divided style of life is clear: As Sonia reminds us, she is ‘professionally skilled at holding two things in [her] mind at once and choosing which to look at as felt convenient.’ Unfortunately, it is hard to identify with or root for Sonia, making the whole story feel slightly remote, and the extensive borrowing from Hamlet itself contributes to this.

The theatre cast become a more coherent company by the end, and there’s an increasing sense that they operate similarly to Greek chorus, commenting on the action taking place in Gaza. As opposed to singing in unison, however, they represent various groups - 48ers who live within Israel, Sonia herself who is something of an outsider and so on. For me, the focus was too scattered between characters to create a rounded sense of any of them. This Arabic version of Hamlet, and the play for Claudius within, are presented as a form of resistance, as they have been in real life in many sites of oppression around the world. Sonia taking the role of Gertrude symbolises her developing identity into which she starts to express a sense of being Palestinian as well as Dutch and English, investing in this part of her culture by joining a demonstration with her sister. A story is hinted at about the experience of women specifically, ending with Mariam herself taking the lead role of Hamlet, but this idea doesn’t feel fully realised.

The novel as a whole reads as crafted, controlled, perhaps unsurprisingly from such a celebrated, award-winning author. The relationships between sisters, friends, actors, lovers are problematic, feeling tenuous and performative or superficial much of the time, but occasionally seeming more authentic and resilient. As a study of failed, strained and contingent relationships, it works but lacks warmth.

I didn’t love this, partly because I don’t love theatre as much as other forms of art, and didn’t feel persuaded that this production was the battle to pick, but perhaps that’s cowardly. However, it did provoke thought concerning the necessary conditions for genuine communication between humans. Will Hammad win the prize this year? You could argue that her novel’s scope and ambition is greater than that of ‘Soldier Sailor’, and it’s of more contemporary relevance than ‘Restless Dolly Maunder’, but I’d say no. As a reader, I felt more distance, less recognition. I learned a little, but was never really surprised conceptually or emotionally by the plot. Definitely worth a read, but not, for me, a winner.